6 Totally Real Reasons Arkansas Needs Houston Nutt

So that’s it. After just under two agonizing years, Chad Morris is out as the Hogs’ coach. I’ve been a Razorbacks fan for my entire life, and I can tell you this: coaching searches haven’t been good to us over the last few years. It’s time we look back in order to move forward into the future of Arkansas athletics (and definitely not to THIS GUY)

There’s one solution to our problems, and that solution has four letters: N U T T! Here’s 6 of the infinite reasons why a guy who hasn’t coached in half a decade should be our next ball coach:

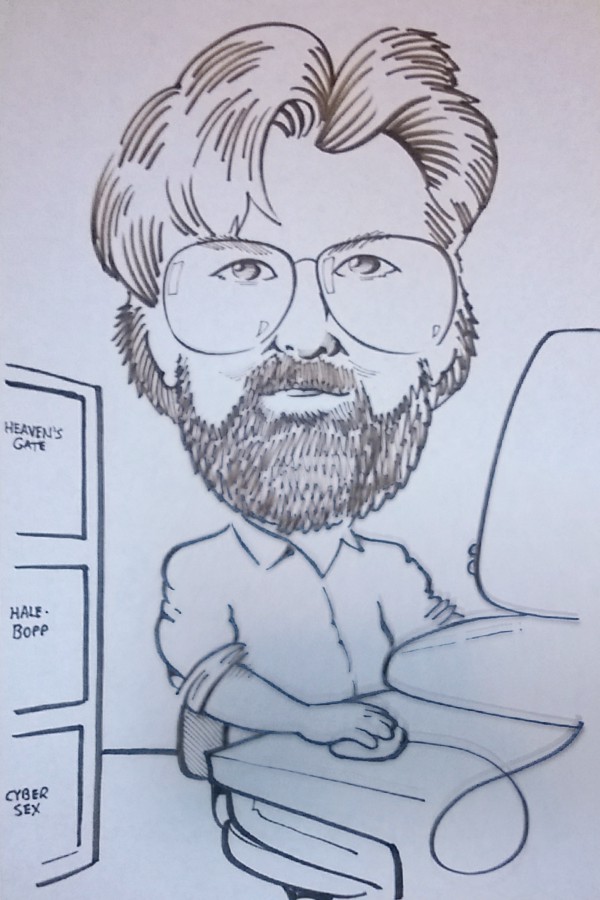

1. Look at this guy right here. That’s a football coach.

No further explanation needed.

2. He’s in the people heppin’ bidness.

I don’t know about you, reader, but after two years of the Bobby Petrino Show, the Gas Leak Year of John L. Smith, five years of forgettable mediocrity under BERT, and then two years of abject agony under Chad Morris, I need a bit of heppin’.

3. He brought the guy who brought dat wood.

Every time I try to explain this photo to people, they get very confused and ask me why a football player is holding a mini baseball bat. Then I have to explain the ‘dat wood’ thing, and then it just gets confusing. Anyway, I love Darren McFadden so much I have a signed copy of NCAA Football 2009 for Xbox 360.

Remember Darren McFadden? Remember when we had three guys in the backfield who were all monsters and we found a way to give them all the ball in situations where they could play to their strengths instead of sacrificing a really talented running back in service of a scheme that was obviously not getting the job done (definitely not referring to Rakeem Boyd’s less than a dozen touches against WKU or anything)

4. He’s such a prolific recruiter the NCAA had to make a rule to slow him down.

I can’t hear you over the sound of your massive buyouts, Yurachek!

It’s the Houston Nutt Rule. Need I say more? There’s no Chad Morris rule…

5. He knows how to put up with our bullshit.

Imagine feeling this way about Hogs football again.

Let’s be real, there’s a very particular kind of expectation at Arkansas, given that you have a whole state’s attention and a lot of perpetually unhappy boosters. Coach Nutt survived ten years - longer than most other coaches could dream about - while bringing home a couple of SEC West titles.

7. 50% W/L in the SEC sounds pretty damn good right now.

We, stupidly, fired this guy after he BEAT LSU.

In his worst year, Houston Nutt went 4-7 and missed going bowling for the second year in a row. Houston Nutt’s Hogs were often good, sometimes great, middling from time to time, but never AWFUL.